Every year on March 17th, we commemorate the invention of the rubber band, patented by Stephen Perry in 1845. This innovation followed Charles Goodyear’s groundbreaking discovery in 1838 that adding sulfur to polyisoprene creates crosslinks, significantly enhancing its elastic properties. This breakthrough led to the development of rubber tires.

Composition of Rubber Bands

Rubber bands are traditionally made from polyisoprene, a polymeric elastomer derived from either the latex sap of rubber trees or petroleum products. They can also be made from ethylene propylene diene (EPDM) rubber and silicone. Polyisoprene rubber bands are prone to degradation, especially when exposed to sunlight, which causes them to become brittle over time. In contrast, silicone and EPDM rubber bands are more resistant to degradation.

Elastic Properties

Rubber bands are almost purely elastic, meaning they return to their original dimensions after being stretched and released without any permanent deformation. This elasticity is due to the crosslinks in the rubber that connect adjacent long polymer chains, forming a three-dimensional network. This process can be repeated multiple times without causing permanent deformation.

Thermal Dynamic Principles

In the mid-1800s, Lord Kelvin developed the theory of thermodynamics using rubber samples as examples of entropy principles. James Joule confirmed Kelvin’s theory with experiments showing that rubber samples increase in temperature when stretched. Two key principles underlie the thermodynamics of rubber bands:

- Internal Energy Independence. The internal energy UU of a rubber band is independent of its length L0L0, expressed as U=cL0TU=cL0T, where TT is the temperature and cc is a constant

- Linear Tension Increases. The tension σσ of a rubber band increases linearly with its length, given by σ=bTΔLσ=bTΔL, where bb is another constant and ΔLΔL is the change in length.

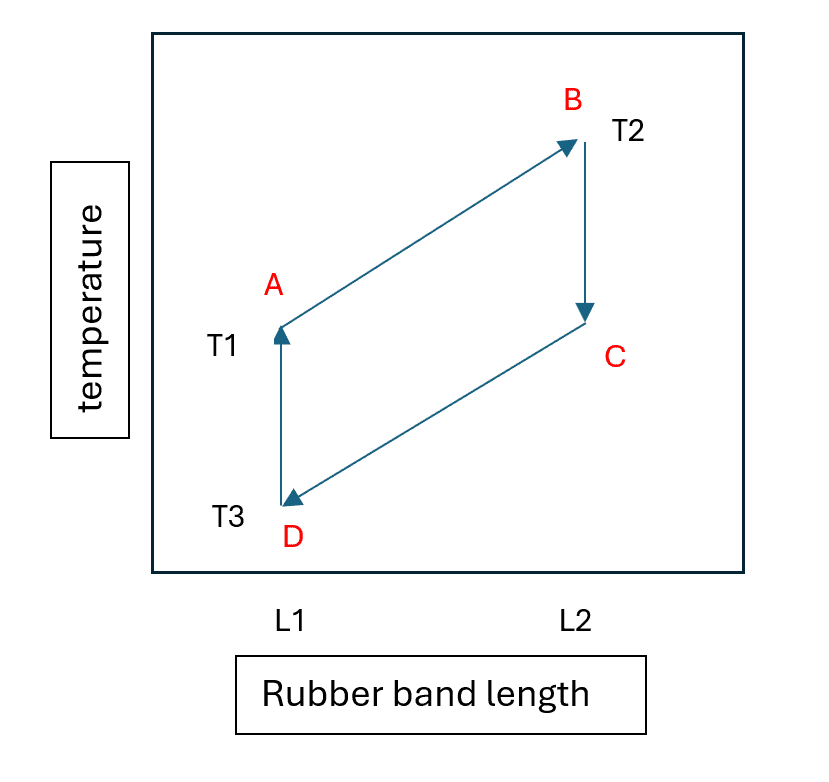

Kelvin described the thermodynamics of stretching a rubber band using the Helmholtz free energy (AA) expression: A=U−TSA=U−TS, where SS is the entropy of the system. AA represents the total energy available to do work. The internal energy UU includes potential and kinetic energy, expressed as U=Q−WU=Q−W, where QQ is heat added to the system and WW is work done by the system. Heat transfer can be written as dQ=TdSdQ=TdS, and work done on the rubber band as dW=σdLdW=σdL. Rearranging these expressions yields dF=σdL−SdTdF=σdL−SdT, where dFdF is the change in free energy, dLdL is the change in length, and dTdT is the change in temperature.

The temperature change in a rubber band is given by dT=dL(σ/S)−dF(1/S)dT=dL(σ/S)−dF(1/S). When a rubber band is stretched (dLdL positive), its temperature rises. Conversely, when it relaxes (dLdL negative), its temperature falls. At points where the rubber band is held at a fixed distance, heat either dissipates into the environment or the environment warms the cooled rubber band.

Molecular Alignment and Entropy

On a polymeric level, stretching a rubber band aligns and orders its molecules, decreasing entropy. When the rubber band relaxes, the polymer chains also relax, increasing entropy again.

Experimenting with Thermodynamics

You can easily demonstrate these principles by lightly placing a rubber band against your lips, which are sensitive to temperature, and moderately stretching it. You should feel a temperature rise. When the rubber band is relaxed, a cooling sensation should be noticeable. This simple experiment illustrates the effects of microscopic molecular motion.

Remember to wear safety glasses when conducting this test.